75 years ago the Germans set fire to the National Library in Warsaw

During the Warsaw Uprising in August and September 1944, when the inhabitants of Warsaw rose up against the Nazi occupiers, the losses to Polish troops amounted to approximately 16,000 people killed or missing, 20,000 injured and 15,000 taken prisoner. As a result of airstrikes, artillery shelling, harsh living conditions and massacres organised by the German troops, between 150,000 and 200,000 civilians in the capital lost their lives.

Following fighting by insurgents and the demolition of the city by the Germans, most of the buildings on the left bank of the Vistula in Warsaw were destroyed, including hundreds of priceless monuments and objects of great cultural and spiritual value.

Some 75 years ago, on October 14, 1944, following the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising and the expulsion of the civilian population, two Polish librarians – Ksawery Świerkowski and Leon Bykowski – taken by Gestapo (German secret police) officers to examine the state of cultural institutions during the destruction of Warsaw, witnessed the burning of the most valuable collections of the National Library and other Warsaw libraries in the modern warehouse of the former Krasiński Library on Okólnik Street.

Following this brief visit, it was not until November 1944 that it was possible to enter the warehouse and assess the magnitude of the losses. Professor Bohdan Korzeniewski described his impressions as follows: "The descent to the cellars was not cluttered with debris. I was able to make it to the dungeon. At first glance, I could experience a sense of stunned joy. »The collection has survived« I wanted to shout out. It lay there in various thick layers. The sense of order was somewhat striking – we had not left them in such order when disguising the entrance to the shelter. There were no metal sheets, no sandbags. Also striking was the fact that the layers appeared to be much lower now. The volumes no longer reached up as far as the vaulted ceiling as they had done when we placed them there. Closer inspection revealed the reason behind this alteration. It was hideous. Touch a layer of the evenly arranged copies and they didn't fall apart – they vanished! The collection had been completely consumed by the fire, which must have devoured them slowly over many days. It wasn't hard to guess how they were destroyed, either. The members of the Brennkommando or the Vernichtungskommando or whatever those State-sponsored gangs of thugs were called no doubt had plenty of experience. They also had plenty of time to do their work now that Warsaw was defeated. They had pulled the books out from under the ceiling, poured petrol on them and set them on fire. They already had their feet on the throats of our neighbouring nation and were busy carrying out the sentence of extermination they had imposed on them. Besides being capable of genocide, they were also capable of libricide."

The description given by Tadeusz Makowiecki is similar: "Silence. All the windows of the warehouse are black and empty. But we know that the Library survived the Uprising. We descend to the huge cellars, our shoes sticking in the ashes. They must have each been set fire to separately, systematically. This was where the greatest treasures were collected: manuscripts, early printed books, drawings, engravings, musical manuscripts, maps, the Załuski Library [the first Polish National Library, the largest in Europe in the eighteenth century], the collection of Stanisław II Augustus, the remnants of the Rapperswil Collection, the Krasiński archives, the treasures of all the Warsaw libraries. Nothing. Nothing. [...] Once again, one feels this is just too much, as at the cruel reports of loved ones lost. Powerless, we drag ourselves along the dark corridors of the cellars. In the deepest room, the large boiler room, there are maybe as many as a hundred wooden crates – quite empty (ready for evacuating the collections). They were the only thing the Germans didn't set fire to. But why? We stand there, lighting up the vaulted cavern with a few candles. Finally, we take the empty crates, two each – they will be useful in other libraries – and slowly move on. Stumbling across the rubble, passing through the mountains of bricks to the level of the first floor, we walk across the street in silence, a cortege bearing ten long wooden crates – empty, not even with ashes in them."

The National Library, one of the largest and most valuable libraries in Poland and indeed Europe, had prepared for the coming war with a number of security measures. The 22 manuscripts considered most valuable for Polish culture and history were removed from the National Library building in two trunks on August 5, 1939. They included medieval works such as the Rocznik świętokrzyski dawny (the Old Annals of the Holy Cross, containing the famous Latin sentences marking the very beginnings of Poland, "Dobrawa came to Mieszko" and "Mieszko was baptised"), the Saint Florian Psalter made for Queen Jadwiga, the Kazania świętokrzyskie (Holy Cross Sermons, the oldest prose record in Polish), the medieval chronicles of Wincenty Kadłubek and Gallus Anonymus, and a portfolio with handwritten musical scores by Frederic Chopin. These manuscripts, together with other valuable items set out from Warsaw on September 6, 1939 on their long journey to safety in Canada. There, they survived.

The National Library suffered its first losses during the German air raids of September 1939, despite the selfless work carried out, moving the collections to the basements. At this point the National Library lost, among other things, some 800 manuscripts and 30,000 volumes from the renowned Rapperswil Library, together with 250,000 volumes from the Central Military Library, where it was being stored.

On February 1, 1940, the National Library was closed by the occupation authorities. Between July 1940 and February 1941 the Germans created the "State Library" (Staatsbibliothek Warschau) in Warsaw, which included the National Library, the University Library and the Krasiński Library, alongside many libraries belonging to institutions that had been shut down. The collections of the National Library were to remain closed to readers. The most valuable collections (manuscripts, early printed books, drawings, engravings, maps, musical scores) from the above-mentioned libraries were gathered together in the modern warehouse of the Krasiński Library on Okólnik Street. Thefts by the Germans and the removal of individual valuable items as well as larger collections continued throughout the entire German occupation of Warsaw.

During the Warsaw Uprising, part of the collection was burned, but a huge collection of the most valuable objects was kept in safety by Polish librarians in the basements of the building, where they survived.

Point 10 of the Agreement on the Cessation of Hostilities of October 2/3, 1944, which ended the Warsaw Uprising, states as follows: "It will be possible to evacuate objects of artistic, cultural and ecclesiastical value." However, the Germans in fact prevented the collections being evacuated. Most likely on October 12-13, 1944, the Brandkommando of the Wehrmacht (Nazi German army) burned collections of the most valuable literary monuments from the National Library in one of the greatest losses to Polish culture in its history, and one of the greatest losses to written culture in history of the world.

The National Library lost at least 39,000 manuscripts – and most likely more, perhaps as many as 50,000 – along with some 80,000 books from the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries, 100,000 books from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, 60,000 drawings and engravings, 25,000 musical scores and 10,000 maps. The great family libraries were almost wiped out, such as the famous collection of manuscripts of the Krasiński Library, of which just 78 volumes survived out of more than 7,000. Few of the most valuable Warsaw collections could be saved. The nineteenth and twentieth-century collections of the National Library housed in the SGH building on Rakowiecka Street were somewhat more fortunate.

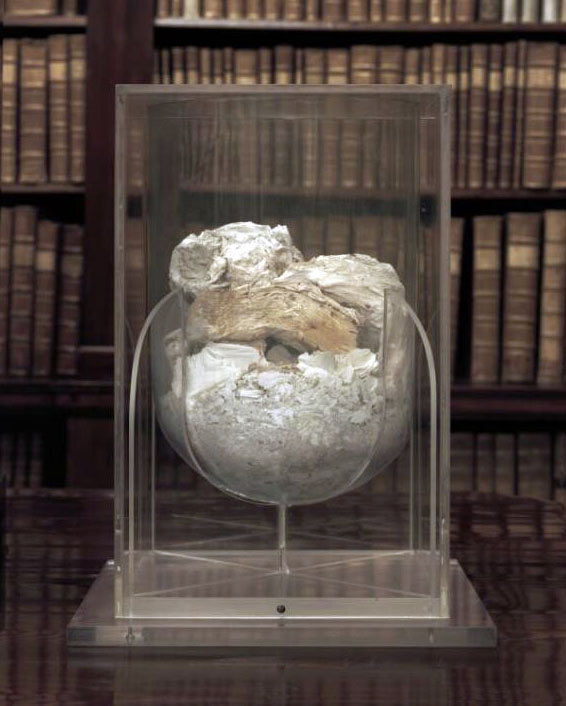

75 years ago the librarians placed the ashes of the most valuable collections of the National Library in a transparent urn. The rough shape of the volumes of the unique books and manuscripts can still be seen today, but no one will ever be able to read them.